One time, Jon at Blurbomat blogged about what it meant to him to be a father. (Edit: Jon’s post can be found here.) I can’t remember all the details of what he said, but his main point was that whatever freedom to pursue his artistic self-expression he’d given up, he had no regrets, because his family was the most important and fulfilling part of his life. I wrote him (I have no idea if he ever read my e-mail), because that day I read his blog over and over with tears streaming down my face.

My dad was born to a prominent (not wealthy, just old) family in a small Southern town. Basically that meant that he could have hung out and been who he was and no one would have expected him to be anything else. Instead, he lived several lifetimes by the time he’d turned thirty. He worked with the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Depression. He traveled throughout the U.S. by hitching rides on rail cars and ate meager meals with hobos next to campfires. He was skilled with a paintbrush, so sometimes he made a little money by painting signs for businesses and towns. Later, like many young men his age, he joined the military. He landed at Normandy on D-Day. He was for a time behind enemy lines in Holland, and along with some fellow troops, was hidden by a Dutch family. He helped take a town for the Allies, during which mission he removed a gun from the trembling hand of an old German man who was pointing it at him as my father turned a corner. They both walked away alive. His infantry division also liberated a Nazi death camp.

He came home a changed man to the family and town that loved him. He never called himself a hero. Like so many other soldiers, he would say, “The real heroes are dead.” He drifted a little, I think, and maybe he painted a little. And then he met my mother. She wanted more for him than he wanted for himself. She urged him to take advantage of the G.I. Bill and go to college, which he did, with a double major in art and history. Throwing a group of ex-soldiers who’d seen hell into a mix of babies who had no idea what the world was about–it was often the stuff of great comedy. He was far more willing to tell us stories of his college years than his war years.

While my parents were in college, the first two babies came. Finances were a struggle, and when he graduated, his teaching job barely provided for them. So he went back into the Army and made it his career. There were tours overseas (I was born during one of those). There were stints turning new recruits into soldiers. And finally, before retirement, a couple of assignments teaching military history to college students.

After retirement, he taught school again. Was an assistant principal. Became a small-town mayor. He wrote stories about his past. Through all those years, whenever there was time and money for supplies, he painted. His art–that passion of his youth–had become a hobby. Like any neglected gift, it became uneven. Sometimes his work was very good. Sometimes it was mediocre. Finally, in failing health, including tremors caused by Parkinson’s Disease, my father retrained himself to use his left hand instead of his right. That, too, affected his art. By the time he died–on April 18, 1985–he hadn’t left a large body of work. However, when I look at photos from my childhood, I realize there are a lot of paintings whose whereabouts I don’t know. I hope someone who appreciates them has them.

When I began my own artistic journey in earnest (i.e., actually writing, and not just talking about it), I found that I often wondered about him. I wondered if he regretted putting his art aside to make a living for his family. I wondered if he ever resented us or second-guessed his choices. Sometimes when I’m working, I have interior conversations with him and try to imagine that I get to ask him questions that it never occurred to me to ask when he was alive.

And so that day when I read Jon’s blog about being a father, I felt like I was getting an answer. I thought of what a really good father I had. Not perfect, but someone who put unselfish thought into how he guided his children and grandchildren. I thought of all the young soldiers who kept in touch with him over the years. I thought of the students–some of them my own classmates–who told me wonderful stories about him. And I knew that a person who was filled with resentment and regret could never have impacted so many lives in such a positive way.

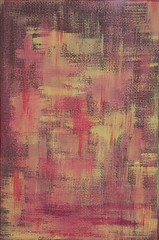

Mark asked a few days ago if I might consider posting photos of my “art collection.” Maybe one day. But for today, on this anniversary of my father’s death, I thought I’d share a photo of what is probably my favorite of his paintings. He did it specifically FOR me, which makes a difference. I told him I wanted a painting of a city, and this was his interpretation. I watched it progress, and I loved it from start to finish. And for some reason, he gave it to me without signing it. From time to time, I’d remind him that he needed to sign it, and then we’d forget. After he died, I was telling someone–it may have been Tom, now that I think of it–how he’d never signed my painting, and then I looked up and saw in the right corner a very faint “Cochrane.” It was shocking and wonderful, a little gift I never knew he’d left for me.

The City

I think of my father every single day, and though I don’t consider myself an artist, I especially think of him when I paint. One night I sat across the table from Tim and worked on one of my tiny OneWordArt canvases while Tim was painting. It wasn’t until I was finished and thought, Why does this seem familiar? that I turned and saw the painting on the wall next to me. I smiled at that connection, and the word I chose to title my painting was “Respect.”

I think the reason is obvious.

Respect

What a wonderful story. I think that the paintings are interesting, and how you made one so similar to his, at first, without even knowing. The connections we have to people run deep, even if we sometimes don’t realize that.

Thank you.

🙂

that’s it.

You say a lot even when you say a little. =)

well, it’s really cuz i can’t quite put into words what all i mean and think about something. but i’m glad you understood. 🙂

Becky, girl you have a knack for making me cry when you write, fiction or fact.

I love your Dad’s painting. I will keep an eye open for them locally. If I see one in an office or a home, I will ask if I can photo it for you. It was news to me that your father was an artist. I knew the mayor and (part of) the military part.

Thanks for sharing.

Thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed it. And thanks again for “Tribute.”

What a beautiful story and paintings. What a wonderful way you have of expressing yourself. Becky, I’m just soooo moved by this! I don’t even know how to tell you.

My own father was gone most of my life and re-entered it the winter before I gradutated high school. He and mom remarried and I had 16 wonderful years with him before he died.

Oh, I’m so glad you got that time! That’s quite a story, too.

Thank you.

Ours was a rocky relationship, at first, because the “rules” were different. We loved each other, but when you start the relationship as adult, rather than child/adult, it makes for some interesting challenges. I only wish I had come out to him before he died. The day of his funeral, I got to the funeral home before anyone else ans stood there at his casket and told him everything about me…the men I had loved, the heart breaks I had had, and how who I loved wasn’t important, only that I had loved and been loved in return. It felt good.

I’m glad you shared all that with him–and told me about it. It’s never too late to talk to someone with whom we’ve shared a deep love.

I know he’d be very proud of you.

Anonymous would be me, of course, too sleepy to remember to log in.

Thank you.

Awww…

That’s just, awesome.

I can’t tell you how much I love stories like this one.

This man sounds incredible. What was his sense of humor like, Becky? And was the story of how he met your mom a romantic one?

Other than a tendency to tell really bad jokes, his sense of humor was fine. And a little bit of their first meeting is actually embedded in one of our books. Yes, it was romantic.

Two beautiful posts…the one that inspired it, and this one.

Thank you. =)

What a wonderful gift your dad has left you.

=)

I love your post, loved reading about your father, and loved both paintings.

Also, thanks for mentioning the Blurbomat post — I went back and found it, and it was beautiful.

Thank you. =) I should have linked his exact post, but fortunately, his archives are probably not too cumbersome to get through.