Current Photo Friday theme: On The Road

New Orleans, May 2013

Comments are appreciated and answered.

Current Photo Friday theme: On The Road

New Orleans, May 2013

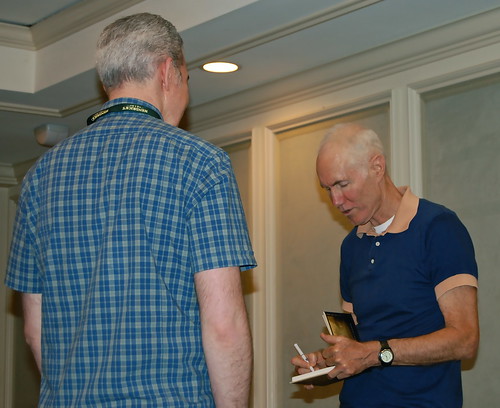

The last panel I attended at Saints and Sinners was “State of the Art: LGBT Writing Past and Present.” The panel was moderated by Thomas Keith and the lively discussion was driven by Dorothy Allison (Bastard Out of Carolina; Cavedweller; She Who), Andrew Holleran (Dancer from the Dance; Nights in Aruba; The Beauty of Men; Grief), Val McDermid (author of 26 novels including The Vanishing Point; Wire in the Blood; Fever of the Bone), and Felice Picano (The Lure; Ambidextrous; Like People in History; Onyx; Late in the Season). This is one of those events about which I’m going to say–not meaning to be either coy or cruel–that you had to be there to fully appreciate the personalities of the panelists and the passion of the discussion.

What makes a piece of writing LGBT? Is it the sexual orientation of the author or the theme of the writing? For example, there are writers who identify as gay or lesbian who write mainstream fiction without gay characters or themes. There are gay and lesbian writers who write fiction with primarily gay characters and themes. There are straight-identified writers winning awards for novels about transgendered, bisexual, or intersex characters. There are writers who identify as straight writing mainstream fiction with secondary gay and lesbian characters. There is fiction which takes place primarily in gay urban enclaves with almost all gay and lesbian characters, and no one is exactly sure who writes it because the authors’ names are initials or gender neutral (“It’s Pat!”).

You might be asking what difference it makes, which means you’ve probably never been witness to the (figurative, I hope) blood baths that happen when these questions are discussed among writing groups as applied to getting published, finding readers, and winning literary awards. I’ve seen my own writer name bandied about in those battles a time or two, and I don’t have much desire to refight them, but it’s never good to make assumptions about my point of view. If you didn’t hear something from me, you don’t know what I think. And at that, what I think may evolve.

When publishing is talked about in general terms–as in, all publishing, not related to particular niche markets or genres, or even format (newspapers, for example, as well as novels and short story collections)–I often think of the history of commerce during my lifetime. When I was growing up among the small towns of the Southeast, we generally had a “downtown” or a town square, where most of the merchants were located. To shop, we walked in the open air from one store to the next. Most businesses were locally owned, and even if they weren’t (Western Auto or Sears, for example), they were franchised or managed by people we knew. The sun or rain beat down on you, and you stopped into the drugstore or the local sandwich stop for lunch or even just a cold Coke, then you finished your shopping (or “just looking”) and piled into the car and went home. If you lived in a larger city, there were shopping centers: an L shape of mostly locally-owned stores around a parking lot, often anchored by a grocery store for one-location shopping.

Then came the great reign of the malls, when all the stores were inside and the climate was controlled and music was piped in. You might still know a few managers or merchants, and mostly you just wandered, a little dazed, with the sound of water splashing in a center-court fountain where you dropped pennies and wished for more money to buy more stuff. You might even forget what city or town you were in, because malls, even with different anchor stores, were generic: department store(s), gift stores, novelty stores, home decor, maybe a store that sold pianos where an employee sat, day after day, playing alone, because almost no one went inside, gender-specific fashion stores, a jewelry store or two, and around it all a parade of seniors walking in their pastel track suits during the day and groups of bored teens on weekends and summer days–mostly in the food courts and arcades.

Then the super discount chains began to steal customers from the malls: Walmart (and for a while, KMart), Sam’s Club, and Costco, where you could also sometimes buy gas for the cars you had to drive to get to these monoliths. Then people began to complain about where the merchandise comes from and how the buildings themselves are a blight on the landscape, and suddenly, popping up in the suburbs, came artificial town squares and outlet malls, places with landscaping and brick “streets” where shoppers walked from store to store in the open air and dashed into a sandwich shop…

Everything old is new again.

There used to be a few big publishers and they wouldn’t touch LGBT-themed books because they were controversial or they thought they couldn’t sell them. Small presses formed to give LGBT writers a chance to tell their stories and market them. And they did sell, and as these marginalized groups fought for and won more visibility, along with the writers who wrote about them, the big publishers caught on and some of those writers were published to acclaim and awards. Then the small independent bookstores that once sold titles for and to that limited market (and other limited markets) were gobbled up or run out of business by the chains and big box stores that could stock more titles. Except publishing also changed, because, according to some observers of the marketplace, other entertainment was available 24/7 so people weren’t reading as much. The big publishers with high overhead struggled and the brick-and-mortar stores, blaming e-books for their diminishing business, began to sell non-book merchandise and when that didn’t work, to close, and nobody wanted to publish anything unless they thought it was a sure seller (written by someone with a proven track record or a celebrity or at least someone with a TV show of some sort)–and where did all this leave LGBT writers or LGBT-themed books?

Into the breach arrived the small presses. And the university presses. We’ve been here before: see above.

Some of the best books I’m reading may have a limited print run or be available only as e-books, but as I said in an earlier post, if you write something good and you are persistent, you can find a publisher. People still love to read, and in time, more people will discover or develop that love and they will buy books, and good books will sell more than bad books, and because of that, the work of editors will be valued again, and well-edited books will sell more than poorly-edited books. The manufacturers and sellers of e-readers are fearing that their market has reached its peak, that readers are already tiring of the novelty, and from consumers, I’m starting to hear more, “I just want to go to a little bookstore where they know me and what I like to read and can recommend and sell me a book. A real book I can hold in my hands and loan to a friend and that no vendor can ‘erase’ from my e-reader because the vendor is mad at the publisher…”

What do I think this all means? That no one really understands this industry in flux, and it will evolve to sustain itself. If the “experts” don’t know, how can you? Write what you want to write. Let your creation begin with love. Treat it with kindness and discipline. Don’t write to markets or trends. Publish what you write the best way you can find. And then–here is the final piece of advice from me that I wish every writer would heed–LET IT GO. I don’t mean don’t promote it (although sweet baby Veg-O-Matic, not every day, over and over, on every bit of social media available to you, because you are alienating the shit out of everyone, including potential readers). Yes, blog it. Sign it. Send out postcards. Whatever. But LET IT GO in terms of, don’t compare your sales to every other writer’s sales. Don’t obsessively read your reviews and engage in discussions–dare I say, fights?–with people who don’t get it or don’t like what you’ve written. You can’t control how your work is received, and not everyone will understand and love everything. Don’t resent other writers whose work (you think) is selling more than yours. Don’t feel like another person’s success robs you. There is room for all the books and all the authors: Books are like drugs. The more people read, the more they want to read, and I can’t tell you how many times, as a bookseller or when attending events related to books, I’ve heard people say, “I read this one book with a (gay or female or teen or detective) character and then I went to my library (or bookstore) to find more books like that.” Every success builds the market and gives you a greater chance of being published and read.

The book that sells a million copies may end up with a disgraced author and can’t even be located in a remainder bin a year later. The little book that never took its author out of obscurity suddenly finds an audience twenty years after his or her death. Hateful comments from a reviewer–or a lot of them–sometimes make a person like me pick up a novel out of sheer orneriness (“If it pisses off the mob, must be something to it!”). As a writer, you really can’t control all of that. You can control what happens when you sit down with your iPad or smart phone or computer or legal pad or Moleskine to write that story.

And then what happened?

This morning I was reading a blogger who provided a list of “unfortunate” things people say to artists. They seemed all too familiar and applicable to writing, as they are designed to make the creative person feel bad about how much time s/he spends on a “hobby,” how much artistic work costs the consumer, and what different choices the creative person should or could make. (“You should paint landscapes.” “You should write a book like Dan Brown.” “You should write pop music.”) I’m sure we’ve all heard these, not only from strangers but from people who say they care about us and who should know better.

The practical challenges of life as balanced with writing was the topic of the Saints & Sinners panel “There and Back Again: Surviving and Loving Your Writing Career.” Moderated by Michael Thomas Ford (What We Remember; Changing Tides; Full Circle; Looking for It; Last Summer; Suicide Notes), the panelists were Trebor Healey (Through It Came Bright Colors; A Horse Named Sorrow; Faun; Sweet Son of Pan), Martin Hyatt (A Scarecrow’s Bible; Beautiful Gravity), Fay Jacobs (publisher A&M Books, author of As I Lay Frying: a Rehoboth Beach Memoir; Fried & True: Tales from Rehoboth Beach; For Frying Out Loud: Rehoboth Beach Diaries), and Jess Wells (writing teacher and author of The Mandrake Broom; AfterShocks; The Price of Passion).

This panel was filled with so much lively discussion that there’s simply no way I can do justice to it all. So here are some key points that I took away.

You can be published. There’s no conspiracy to keep your work away from the public. There’s no clique you have to join to have your writing read and accepted for publication. If you write a good story or a good novel, it will find a home. But first, you have to actually write it, not talk about it, not resent others who are doing it, not make excuses for why you’re not. And then you have to hone it, using beta readers, paying proofreaders, joining writing groups, attending writing workshops, whatever it takes. Then you have to submit it. The burden is on you to find your market. It’s easier than ever with the Internet to find agents to query, calls for submissions, addresses and guidelines for small presses, university presses, and mainstream publishers or periodicals that publish shorter works. And if you don’t want to put all that effort into finding someone to publish you, publish yourself. It’s never been easier to do that, either, and it’s no longer cost-prohibitive as were the vanity presses of old. Once again, the Internet has provided opportunity in the form of e-publishing.

In all likelihood, a lifelong writing career won’t be easy or lucrative. You may have to keep other jobs, or a series of jobs, for an income that will keep a roof over your head and food on your table, or provide you with health insurance or medical care, pay vet bills and buy your clothes and some degree of entertainment in life. This may require creative juggling, but it can be done. A lot of prioritizing goes into being creative, and sometimes forming a supportive community with other creative people can benefit everyone. That doesn’t mean someone else will pay your bills (unless you have wealthy creative friends, and that’s kind of rare), but it does mean that sometimes you can help one another out with a meal, childcare, a ride, bartered services, or just as necessary, an encouraging and understanding ear.

Just because you often work in your pajamas doesn’t mean you don’t have to be a professional. Regard yourself and your work as having worth and behave accordingly. Don’t be petty and jealous and snarky about other people’s success. The writer you’re being a jerk to may be editing an anthology you could submit to next year. The quiet person in the corner who’s listening to you belittle your peers may be an editor at a publishing house in Manhattan. That guy you shoved aside to get to the Famous Writer at an author appearance could be looking for novels to turn into screenplays. That person you didn’t push the OPEN button for as the elevator doors were closing may be a bookseller who’s part of a word-of-mouth network that can help build your career. That unknown ISP address reading the badly spelled and poorly punctuated diatribes on your blog may be an agent willing to represent new writers.

Believe in your work. Believe in yourself. Know that there will be disappointments. The story that’s rejected. The book deal that falls through. The publisher that closes. Know there are costs to any art, and honestly, they never stop. The musician pays for instruments and lessons, the vocalist pays for voice coaches, the artist and sculptor pay for materials, and the writer pays for classes and research and usually a computer. And sometimes there’s a cost to get our work out there: the CDs to sell at the bar where your band plays, the fee to exhibit at the art fair, the cost of a writer’s workshop or some editing services or cards to promote a book signing.

Only you can decide if you want to take this on. I’m relatively sure every person who was sitting in that room with me, panelists and audience alike, believe that if writing is your passion, it definitely is all worth it.

Over the last year or so, I’ve had a lot of fun reading Timmy’s The Idea Jar writing prompts and ‘Nathan’s #canadawrites tweets. Many of them sound like great first lines. Writers also find good first lines in news stories, overheard conversations, and our own verbal reactions to some life situation. (“I hate Christmas!” I complained to a few coworkers a couple of decades ago, and one of them said, “How can anyone hate Christmas? I worry about you.” Many years later, “I hate Christmas!” I said to Tim, and “There’s your first line,” he answered.) Whether you plot out your entire story in advance, write it as the Muse hits, or share it as a spoken anecdote first and then write it, you need to hook your reader from the very beginning.

Once you have your first line: then what?

In media res literally means “in the middle of,” and is a writing technique in which a narrative–whether a short story, novel, play, epic poem–begins at its midpoint. (This also applies to film, but I’m a writer, not a filmmaker.) Most agents and editors will tell you that nothing is more deadly boring than receiving a manuscript that offers basically an “in the beginning” start, a ton of exposition of world building and back story, and somewhere around page 43 finally offers up some action. In fact, most of those readers never make it to page 43, and there went your literary dreams into the recycle pile.

At Saints & Sinners, I went to “Miniature Gems: Crafting Successful Short Fiction” because I edit short fiction, and I rely on an intuitive sense of what works when I read it. I say intuitive, but I’m sure it’s derived from my zillion years of reading, studying, and writing critically about short stories, and my fewer than a zillion years of teaching them. I was looking forward to hearing short story writers’ perspectives because I knew they’d give me more “feedback” language than comments that make me sound like that one student in the back of the class who obviously didn’t read the assignment (to paraphrase Huck Finn, “The words was interesting, but tough.”).

The panel was moderated by Elizabeth Sanders (founder of Eutherion Press; author of Feux de Joie) and the panelists were Daniel M. Jaffe (Jewish Gentle and Other Stories of Gay-Jewish Living; The Limits of Pleasure; One-Foot Lover), Jen Michalski (Could You Be With Her Now; The Tide King; From Here), David Pratt (Bob the Book; My Movie), and William Sterling Walker (Desire: Tales of New Orleans).

Delightfully, their writing techniques and approaches were as different as the individuals themselves. I say “delightfully” because there really is no one method to start or finish or revise a short story. Over time, writers develop their own systems, and then when they feel stale, they shake it up and do it a different way. One of the panelists often writes a short story the way I do: I create the entire thing in my head first; when I sit down to write it, nothing interferes with the narrative flow. Another panelist starts with an ending, so the writing process entails how to get there. They had their own metaphors for how to set up in media res and what dropping a reader into the middle of things entails. One of those metaphors involved a door. If the real story starts behind the door, why does a reader want to spend a lot of time walking to the door, seeing the scenery, remembering doors from the past, thinking about different doors, blah blah blah. Get your reader behind that door.

On the other hand, you don’t want to hit your readers with the impact of what’s behind the door too soon. Sometimes when Tim and I receive a new story, his first comment to me will be, “Why do I care?” I know then that the writer has forced a situation or characters on him too quickly. If you start with your biggest moment, are the rest of the pages going to be back story or flashbacks? You need to hook your reader with your first line–“I want to read more!”–but you don’t need to give away the best part of your story. Drop the readers into the action, but don’t give them everything. For me, a fine example of doing this right is William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” The reader is at a funeral as the story begins, but he’s not expected to weep or feel sad or sorry. He’s just an observer. Then he begins to get details of the past, not always linear, through other people’s memories and conversations. As the narrative unfolds, he’s learning about the past but also being given foreshadowing. At the end, when a literal door is broken down, the reader is stunned, not because he wasn’t prepared for the truth, but because of that one last chilling detail Faulkner saved for last.

In addition to structure, we talked about pacing. Pacing has to do with the story arc, but also I think with the language itself. There have been times that Tim and I will say, even reading someone’s Tweets, “X has no sense of the rhythm of language.” There is a benefit to reading your own work aloud–not to other people, but to yourself. When you read your printed pages out loud in an empty room, you can literally hear whether the rhythm and music of your language works or not. Do you start getting bored and rushing through certain paragraphs? Your reader will, too. Perhaps there’s too much exposition without anything to break it up. Does the dialogue ring false? Does it sound stilted or unnatural when you read it aloud? Or does it have too many of our spoken speech patterns? We often begin sentences with “Well,” but it’s annoying if all your characters constantly do that, just as it would be if they were always inserting “you know” or “uh” into everything they say, as many of us do when speaking. Maybe one character can have some of those spoken idiosyncrasies, but use them sparingly and don’t let all of your characters sound alike.

As the description for this panel said, “To be successful, writers must take on the spirit and attention of lapidaries, polishing every sentence like gemstones to string together a narrative with dazzling effects.” Our stories are unique, and our storytelling should be, too. But reading other people’s short stories and hearing writers talk about their techniques are opportunities to learn how to polish our writing.

Tim and I led a discussion on Friday at Saints & Sinners titled “Ask An Anthology Editor Anything.” Since it was added late and didn’t make it into the program, we heard a lot of “I couldn’t find your panel! I meant to attend!” afterward. Although I think some of that translates to: “I had too much crawfish étouffée and too many hurricanes at lunch and couldn’t find y’all. Or my hotel room. Who are you, again?” No matter. It was a good discussion with good writers in attendance, and we’ve been sent some new stories because of it, so onward!

On Sunday morning, I attended “Cleanup on Page 23: The Role of Editors and Editing in Your Book’s Success.” This was superbly moderated by Michele Karlsberg (curator of OUTSPOKEN: Gay and Lesbian Literary Series; author of Self Publishing Gay Books). The panelists offered a range of editorial experience and included Jameson Currier (founder, publisher, and editor of Chelsea Station Editions), Michael Thomas Ford (What We Remember; Changing Tides; Full Circle; Looking for It; Last Summer; Suicide Notes), Kelly Smith (publisher and editor-in-chief at Bywater Books), and Ruth Sternglantz (former editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux; currently at Bold Strokes Books).

In our session, Tim and I expressed how being writers affects our approach to editing, and it was interesting at the Cleanup panel to hear the perspective of editors who don’t write. I think we all want the same thing–to find good writers and encourage good writing. Sometimes that requires tough editorial choices–within a story or novel and within a collection of stories. It’s not easy to reject a writer’s work, and it’s frustrating to have too little time to be able to give a lot of constructive criticism.

When I receive a story, I read the first paragraph. If it’s not engaging, I put it aside. If it’s engaging, I flip to the end and read the last paragraph. If it’s mesmerizing, I keep reading after that first paragraph until I get to the end. Though I don’t put equal emphasis on everything, I notice everything: voice, pacing, arc, imagery, character, plot; grammar, consistency, spelling, mastery of how to punctuate dialog; formatting.

What does all that mean to you as a writer? Let someone else read it BEFORE you submit it. Let someone tell you what in your content isn’t working. Find beta readers who aren’t your mom and your best friend. Listen to their input and make decisions about changes without emotion. Get that story or novel in the best shape you can, and then follow submission guidelines. Don’t send unsolicited work if only a query is accepted. If you send work in response to calls for submissions, make sure it adheres to guidelines for length, genre, and theme if one is given.

If it gets rejected, keep working on it. Because trust me, when it gets accepted, you’ll still be working on it with content, line, and copy editors at your publishing house. And when it’s finally published, and you can bear to read it for the two hundredth time, you’ll still find yourself thinking, Wish I’d chosen a better word there. Why did I commit that new writer error, ARGH. Wait–isn’t that supposed to be “led” and not “lead?” OMG, WHO CHANGED FRANKIE SAY RELAX?!?

Good luck!

If Truman Capote’s book In Cold Blood and I were in a relationship, our Facebook status would read, “It’s complicated.” I have alluded to this on my blog before, but here’s the gist of the story.

When I was a senior in high school, In Cold Blood was on a reading list of suggested titles for my English class. I knew my mother had some Capote titles on our bookshelves, so I didn’t think much about it when I checked it out of the library. If you aren’t familiar with the book, it’s Capote’s recounting of the mass murder of a rural family (including a teenage daughter) in late 1950s Kansas. It became the forerunner for true crime books as well as the genre described as creative non-fiction. Putting aside disputed reactions as to its accuracy, this is basically a true event as relayed by a masterful storyteller who understood character, pacing, and setting.

I’m afraid all the literary and socio-economic aspects of the book were lost on seventeen-year-old me. In fact, let me quote myself from a blog post in 2006:

I hate this magnificently written book, and it’s not really a novel, so it probably doesn’t belong on this list. But it took something from me when I was seventeen that I’ve wanted back ever since and have often sought in fiction, so it stays. Funny that Truman Capote was the model for Dill in [my favorite novel] To Kill a Mockingbird. I won’t even see the movie Capote because I’d love to never think of this book again.

I wasn’t able to finish In Cold Blood to do my book report on it. For the first time in my life, I had insomnia, night terrors, and paranoia. It affected my relationships with my family and friends, my attendance and participation at school, and my outlook on life. I kept the truth from my parents for months, until there was just no longer any way I could hide it. Fortunately, my parents took what I was going through seriously and saw that I received medical help. Also fortunately, that medical help included a doctor who said that my terror was less a fear that someone was going to break into our house and murder me than a reaction to all the changes I was facing as I was on the cusp of eighteen and a new life.

This gave me something that I could focus on, work on, discuss honestly, because I felt too ashamed to say, I’m afraid of the dark. I’m afraid to be alone. I don’t want to sleep alone in a room. I don’t want everyone else to be asleep the same time I am. Instead, I could say, “What if I don’t like my roommate? What if I can’t handle college classes? What if I’m homesick? What if I don’t have any friends? What if my professors think I’m dumb?” These were questions that had real answers and enabled the people I counted on to remind me that they would love me and be there for me no matter what. And they seemed like normal problems that any young person might grapple with. Unlike being afraid of the dark for the first time in my life (in fact, I’d been the little kid who loved nighttime and wandered around the house or yard in the dark just because I could).

There was a point that someone–I don’t remember who–suggested that I finish the book to get some sense of closure. I did finish it. And I believe that my family’s patient support, my boyfriend’s understanding, and my English teacher’s kindness saved me (thanks, Mrs. Bryan). But there are residual effects that I cope with to this day, and probably always will.

I rarely talk about the book. I try not to think about the scenes from it that stand out–and trust me, they aren’t lurid scenes. They are simple things chillingly told. That’s the power of good writing. If the old movie that was made from it is on TV and I see an ad for it, I freeze, leave the room, change the channel. When the movies Capote and Infamous came out, it was torment to have to read about them all over the Internet and to be told over and over that I should see them since I love Harper Lee and To Kill a Mockingbird.

This is more personal information than I usually care to share, but I do so to make you appreciate the gift that is Andrew Holleran. I knew Holleran was conducting a master class on Friday at Saints & Sinners. I probably even realized it was about creative non-fiction. But I hadn’t read the description, so it wasn’t until I was planted on the front row and he began talking that I learned that he would be using Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood as the focus of his discussion. I turned to give Tim one wild-eyed look, then I resolved that I wasn’t going to let that book cheat me of anything else.

I learned things I didn’t know. Andrew’s focus was on the writing, the power of the storytelling, how Capote used deliberation and selective detail to create his narrative. I can appreciate all those things, especially as they are discussed by someone with a real understanding and appreciation of good writing.

I came out of the master class with even more respect for Andrew Holleran and a different perspective of Capote’s craft. But still…

That’s why I say, “It’s complicated.”

The panel “Young Adult vs. New Adult: The Complications of Writing for Teens and Tweens” was moderated by Ruth Sternglantz (and as much as I enjoyed her perspective and comments, I also relish her last name, perfect for either a teacher or an editor, I think). The panelists were Trebor Healey (Through It Came Bright Colors; A Horse Named Sorrow; Faun; Sweet Son of Pan), Jeffrey Ricker (Detours; The Unwanted), Sassafras Lowrey (Kicked Out; Roving Pack), and Greg Herren (Sleeping Angel; Timothy).

Though I haven’t written anything specifically for the young adult market, Tim pointed out that we were sometimes writing to a market we weren’t even aware of: the “new adult” market. In this category, protagonists tend to fall within the 18-25 age bracket, and readers are older teens and twenty somethings.

I think when I was myself a young reader, I jumped from tween books to the new adult and beyond categories. Most of the books that were targeted at teens when I was one either bored me (many of them literary classics which I read later as an adult with greater appreciation), or they just rang false. Often they were like the sermons directed toward teenagers in the uber fundamentalist churches I attended–they were meant to scare the hell out of us with horrifying but vague anecdotes–or they were like TV shows that just couldn’t get youth right (“Dragnet’s” hippies come to mind). Since I was the youngest of the voracious readers in our household, there was an abundance of fiction for older readers, and that’s what I read. As a teacher, I taught only literary fiction. Though later, as a bookseller, I became aware of popular middle grade and young adult fiction, I still didn’t read it.

All that is to say it’s not something I know a lot about. As the panelists talked about how to get it right for younger readers, I was struck by one comment: It isn’t the kids who can’t handle frank depictions of sexuality in books, it’s the adults. I won’t go into a rant here about that–and don’t think I couldn’t!–but I will say that I don’t believe things have changed much from my early years in the Paleolithic Age to now in how parents react to what their kids are reading.

I applaud those writers who are weaving good stories around the issues that teenagers and young adults grapple with: loss of innocence, bullying (in social media, schools, and elsewhere), sexuality, teen suicide, family struggles, depression, substance abuse, new relationships, and financial difficulties. As grim as all that sounds, I’m pretty sure the stories also have humor, friendship, romance, and fun, because they’re written by and for real people.

There wasn’t a single panel I attended at Saints and Sinners that didn’t give me a lot to think about, and this was my first on Saturday morning: AIDS Is Still With Us: Telling An Essential Story.

Moderated by Jameson Currier (Where the Rainbow Ends; The Wolf at The Door; Dancing on the Moon), the panelists were Lewis DeSimone (Chemistry; The Heart’s History), Trebor Healey (Through It Came Bright Colors; A Horse Named Sorrow; Faun; Sweet Son of Pan), Daniel M. Jaffe (Jewish Gentle and Other Stories of Gay-Jewish Living; The Limits of Pleasure; One-Foot Lover), and Andrew Holleran (Dancer from the Dance; Nights in Aruba; The Beauty of Men; Grief).

In the early and mid 1990s, the years when I was an AIDS caregiver to several friends, many of the above books and others were essential in helping me understand the politics and social and personal implications of AIDS, particularly as it affected gay men. In fact, sometimes their voices and the stories they told helped me keep my wits in a world gone mad. Fiction and memoir also gave my friends and me a place to begin sharing a language and context with one another. Those books broke down barriers and gave faces and names to what to many people were just statistics that they believed had no impact on their lives.

I remember after Steve R died how I attempted to write several different short stories, and I believe even the beginnings of a novel or two, but I simply couldn’t do it. Everything was too raw, too close. But I think all of those stories–from the caregivers, the ill, the healthy positive, the partners and friends–both old and current, still need to be told. I think there’s public complacency, a sense that because new drugs and treatments have made HIV manageable, that no one wants to read about it anymore. But the compelling stories of populations with rising numbers of HIV infections and AIDS illnesses still have something to tell us about poverty, marginalization, medical care and drug access, and health crises–because AIDS/HIV surely won’t be the last.

I’m grateful these writers and others are still telling the stories. They encourage me to feel that my own voice might join the conversation one day.

Frog Prince.

I was interested to see a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in this tableau. The novel is cited as the first widely read political novel in the U.S.–it was the best-selling novel of the nineteenth century. It has fallen in and out of favor a few times since its release, and is as roundly criticized for the stereotypes it helped create or perpetuate as lauded for its anti-slavery stance. I’ve actually never read the novel, though discussions of it have made me aware of the plot, characters, scenes, and tropes it contains. When considering its role in literature, I could immediately call to mind some half-dozen gay-themed novels written in the 1980s that were similarly simultaneously hailed and castigated.

It’s unsurprising that we still discuss today the role of the novel and the writer in addressing social ills or trying to shine a light on injustice. One of the panels at Saints and Sinners was titled “Beyond the Work Itself: The Writer and Society.” Moderated by Martin Hyatt (A Scarecrow’s Bible; Beautiful Gravity), the panelists included Kenyon Farrow (We Have Not Been Moved: Resisting Racism and Militarism in 21st Century America; Against Equality: Queer Critiques of Gay Marriage), Judith Katz (The Escape Artist; Running Fiercely Toward a High Thin Sound), Sassafras Lowrey (Kicked Out; Roving Pack), and Mimi Schippers (Rockin’ Out of the Box).

The panelists discussed using and maintaining an authentic voice in everything from fiction and essays to scholarly works. Some things they’ve addressed in their work include homeless teens, AIDS, race, sexuality, and gender. It was interesting to hear their perspectives on writing about marginalized populations and how they continue to examine their roles not only as writers but as participants in their communities. It’s something I consider all the time in my writing. I know that most of the novels I read, even the lighthearted ones, can have a point of view that either engages me or enrages me. You?

It is a sad truth that I can be fickle. To all of you who’ve heard me declare my undying love for you or anyone else, I’m sorry. It’s over. I’ve found another.

I first spotted him in a gallery window as we walked down Royal Street. It was love at first sight.

“You don’t like sculpture,” Tim reminded me.

“I like that,” I said.

Unfortunately, the urge toward wine and poolside chat waits for no woman, so I had to hurry to catch up with my friends, leaving The Goat behind. Early the next morning, or maybe the morning after that, I went to visit The Goat again.

Oh, Goat, my Goat,

Why must these cruel panes of glass separate us?

Your enigmatic smile says you might love me, too.

On our last night in New Orleans, The Shop was open when we strolled by. At last! The Goat and I could be together.

The Goat was created by Eugene, Oregon-based artist Jud Turner. You can see better photos of the piece–its true name is GoatHaus—here. Or you can navigate Turner’s entire website starting from here.

I’m reminded that the course of true love never did run smooth. The Goat, at many thousands of dollars, will never be mine. Good thing I’m fickle.