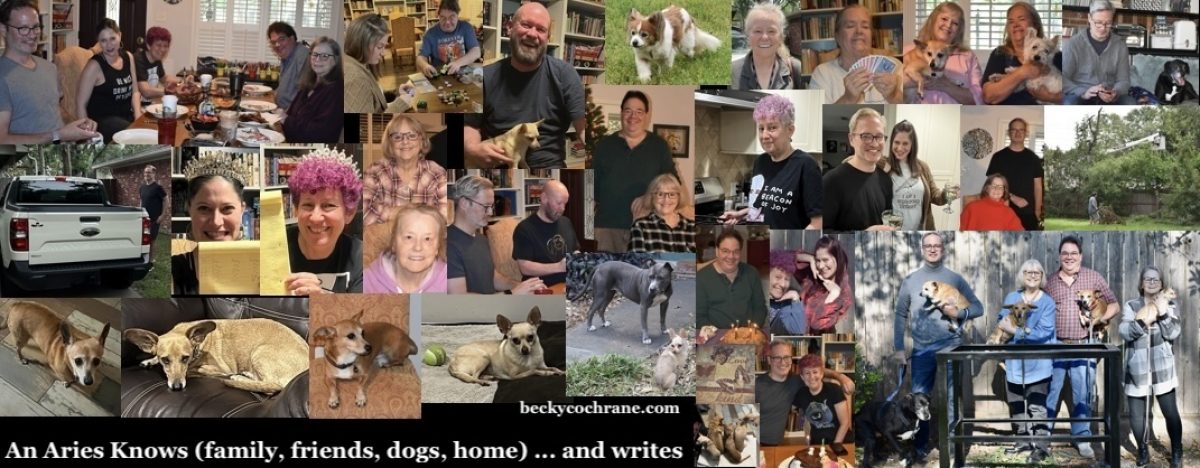

Recently I flung myself back into debt like a good American when I bought a new washing machine for The Compound and a refrigerator for Tim’s apartment. I can’t really complain about these big-ticket purchases because over several decades, I received several new appliances as gifts from family members, and those I’ve had to replace put in many years of good and faithful service before they died.

Sometimes I’m questioned about why I don’t have appliances with all the bells and whistles (I see those things as more stuff that can break and honestly, I just want the basics), or why I don’t have a dishwasher (I never met a dishwasher I liked in my years of renting; I don’t have room for one; and unless I’m really tired, I enjoy washing dishes, and anyway, Tim and Tom–and often our guests–are as likely to wash dishes as I am) or a garbage disposal (not enough room under my sink and not a necessity).

However, this go-round of unexpected appliance buying was annoying because I really, really needed a new computer. Even though computers are completely affordable, I’m tired of doing battle with the firewalls and virus protections that constantly need updating for Windows systems. I have two laptops with Windows if I need to use my existing software, so I’d finally convinced myself to splurge on the iMac I really wanted.

Then the appliance crisis happened. I deliberated about this for a bit, then called to mind the old truism about having children. If you wait until you can afford them, you’ll be childless. Rather than be Mac-less, I threw caution to the wind and after picking out a ‘fridge and a washer, I brought home my new 20.5-pound baby and we’ve been getting along famously.

And then…the microwave died.

Let me back up in time to those days when my first husband and I graduated from college, moved into our tiny house, and were gifted with a brand new washer, dryer, stove, and refrigerator from my parents, his mother, and his two grandmothers. Then one night his stepfather said we ought to have one of those newfangled microwaves. Though I really had no use for a microwave, being a very traditional kind of cook, and saw it mainly as something that would take up space in an already too-small kitchen, in came the microwave.

Every time we turned that thing on, we blew a fuse in our old house. So then came the electrician. Before I could figure out any real use for the stupid thing, scandal rocked our small town. Apparently there was a big employee-theft ring at the local manufacturer of appliances–mainly those newfangled microwaves. Sheriffs were getting tips, knocking on doors, confiscating microwaves, and arresting people. Microwaves were being dumped in ravines, ditches, and creeks before they could become evidence. I called my father-in-law and said, “That microwave wasn’t by chance a little gift to you from an employee of [name redacted], was it? DID YOU GIVE ME A HOT MICROWAVE?”

The microwave was removed from my house in the dead of night amidst much jollity on the part of family members at my paranoia and righteous indignation. I maintained a grudge against microwaves from then on and wouldn’t have one in my house following my divorce and even after Tom and I got married, by which time microwaves were standard in most kitchens.

Then my mother lived with us for a while, and when she moved, she left her microwave behind. Over time, I offered it a somewhat grudging acceptance. It was good for a quick bag of popcorn and to melt butter for my baking. When Tim moved here, he saw it and said, “Where’d your mother GET that thing? From Dolly Madison?” From then on, I thought of it as the First Microwave and liked to imagine a conversation between our country’s fourth First Lady and my mother.

Dolly Madison: Dorothy, the British are coming, and I’ve only got room in my wagon for the White House silver and George Washington’s portrait. Why don’t you take this nice microwave?

Mother: Won’t you need it here in the White House after the War of 1812 ends?

Dolly Madison: Actually, we haven’t been able to use it ever since Ben died and could no longer stand on the White House roof with a kite and a key.

Mother: But most of us won’t have electricity until the 1930s. What will I do with it until then?

Dolly Madison: It makes a handy place to store your bread and BBQ-Fritos.

That dumb microwave outlived my mother, but now it’s gone. I’m not in a hurry to replace it; probably the saddest commentary on how little we use it came when Tom said, “Just make sure you replace it with one big enough for the coffeemaker and toaster to sit on top.”

Friend and cousin Ron contacted me on Friday to let me know that it was time to say goodbye to Kipper. I never got to meet Kipper. I only knew him through Ron’s stories and photos, and I understood their profound friendship. Ron wrote to me about him:

Friend and cousin Ron contacted me on Friday to let me know that it was time to say goodbye to Kipper. I never got to meet Kipper. I only knew him through Ron’s stories and photos, and I understood their profound friendship. Ron wrote to me about him:

Each twitch from you became sound

Each twitch from you became sound I drove your manicure to Starbucks

I drove your manicure to Starbucks

Love Story author Erich Segal died of a heart attack at age 72, his health complicated by his long battle with Parkinson’s disease. The portion of his daughter’s eulogy for him that I’ve read is quite moving.

Love Story author Erich Segal died of a heart attack at age 72, his health complicated by his long battle with Parkinson’s disease. The portion of his daughter’s eulogy for him that I’ve read is quite moving.

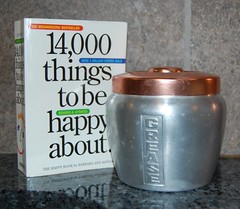

I have confessed on here before that I usually buy my own Christmas presents and tell Tom his part is to wrap them. I know that doesn’t sound exciting, so this year I decided to live dangerously. I told him to buy creative things to put the presents IN. Decorative boxes and such. Proving that men do, in fact, sometimes hear what we say, he remembered that I sometimes opined about the good old days when I, and other family members, used to keep little containers designed for filtering and saving bacon grease. Tom went to an antique store–this is NOT to say that my family members and I are antiques; I’m thirty-five–and found this adorable container to hold one of my presents, which I thought was quite clever.

I have confessed on here before that I usually buy my own Christmas presents and tell Tom his part is to wrap them. I know that doesn’t sound exciting, so this year I decided to live dangerously. I told him to buy creative things to put the presents IN. Decorative boxes and such. Proving that men do, in fact, sometimes hear what we say, he remembered that I sometimes opined about the good old days when I, and other family members, used to keep little containers designed for filtering and saving bacon grease. Tom went to an antique store–this is NOT to say that my family members and I are antiques; I’m thirty-five–and found this adorable container to hold one of my presents, which I thought was quite clever.