I had a run of bad science teachers, and then as a high school senior, I took physiology with the superb Mrs. Rhodes, who I’ve talked about on my blog before. After the thoroughness of her class, and my unbroken streak of “A”s in it, I had no qualms about signing up for my first biology course in college. I had to take four science classes, and the two freshman classes in biology were prerequisites for any others.

There were hundreds of students in my class, which was similar in size to this, but had red plastic chairs and those half-desk tops that flip up:

Image taken from Internet.

I went to every class, took notes, did my once-a-week lab, took my first test–something like 75 multiple choice questions–and couldn’t breathe when I got it back and saw a “D.” Had I somehow skipped a question that caused all my blackened circles on the answer sheet to be in the wrong places? Because I felt like I’d prepared, that I’d known the material.

Next test, I was meticulous about my answer sheet. I finished the test and read every question again, making sure I’d marked the correct answer. Turned it in. Got it back the next week: “C.” People I knew who were taking the same class were making “A”s. What was I doing wrong?

I got tutoring before the next test: another “C.” I managed to get out of the class with a “C,” and I spent my holidays dreading the second survey course. On my first exam in that one, I read the first ten questions and couldn’t answer them. I wasn’t sure if I didn’t know the material or was having a panic attack, but I kept my head down, tears dripping onto my blue jeans. I realized that two different people were deliberately sitting and positioning their answer sheets in such a way that I could have copied from them. Touched as I was by the show of solidarity, I couldn’t cheat. It wasn’t a moral choice. I was just beaten down. I didn’t care. I felt like I was stupid, and the tests were somehow skewed to weed out people with no natural aptitude in the sciences. In fact, rumor had it that this particular professor had missed questions on his own tests, so my mind shut down to him.

I stopped going to class, since no roll was kept. I used someone else’s notes; let other people re-explain the material to me; took my “C”s and was happy to get them. The experience soured me on that side of the campus (the opposite from “my” side, with the literature and history and sociology classes that I loved). During every pre-registration, my stomach would knot when I’d look at the science pages in the catalog or on the schedule. Then someone I trusted took a class called “Earth Science.” He advised me to take it the next semester; I wouldn’t be sorry.

That’s how I ended up with Dr. Neal Lineback, undoubtedly one of the best teachers I ever knew. I never skipped one of his classes. I stopped feeling stupid. And even though I ended up with “B”s, I knew that if I could have written all my answers instead of dealing with multiple choice questions, I probably would have received “A”s. I’d learned a lot about my strengths in the years between science classes, but I also had the confidence that flourishes in students who feel a teacher wants them to succeed.

One of the topics in “Earth Science” was atmosphere, including the study of tornados and hurricanes. It was timely, because we had an active tornado season that spring. Dr. Lineback’s ability to create a learning experience out of the daunting conditions that set off tornado sirens was a gift to us.

I took another course from him in the fall. As the Iron Bowl approached (the big football game between fierce rivals Alabama and Auburn), he broke “teacher” character one afternoon to share something with us. Though he’d gone to a different school in the SEC (Tennessee), he honored the proud football tradition of the Crimson Tide. He evoked the hallowed name of our coach, Bear Bryant. He had us eating up his praise of our school. Then he clapped his hands and said that was enough of that; it was time to get back on topic. He shrugged out of his jacket, turned to the chalkboard, and pretended not to hear the class’s burst of laughter as we saw Auburn’s “WAR EAGLE” battle cry emblazoned across his shirt back.

The only other time he broke out of his lecturer role was the last day of class, when he explained what teaching meant to him. He encouraged any of us who planned to be teachers to bring not only our passion for our subjects to the classroom, but to remember that teachers are actors. They owe every class, every day, their best performances, and if they give that, their students will learn and succeed. Dr. Lineback was later department chair, and then chair at another university, where he is now a professor emeritus. I wish everyone could have teachers with his commitment and enthusiasm.

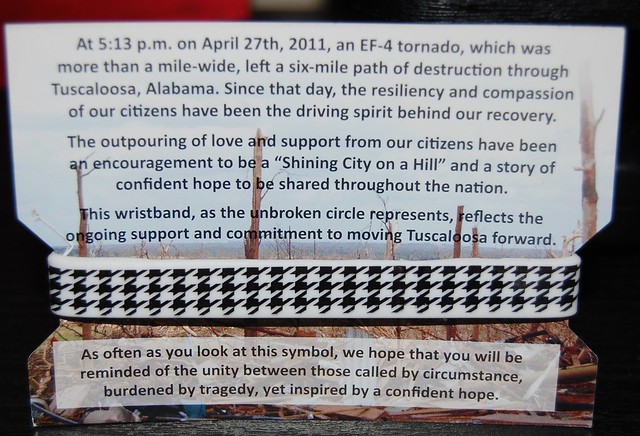

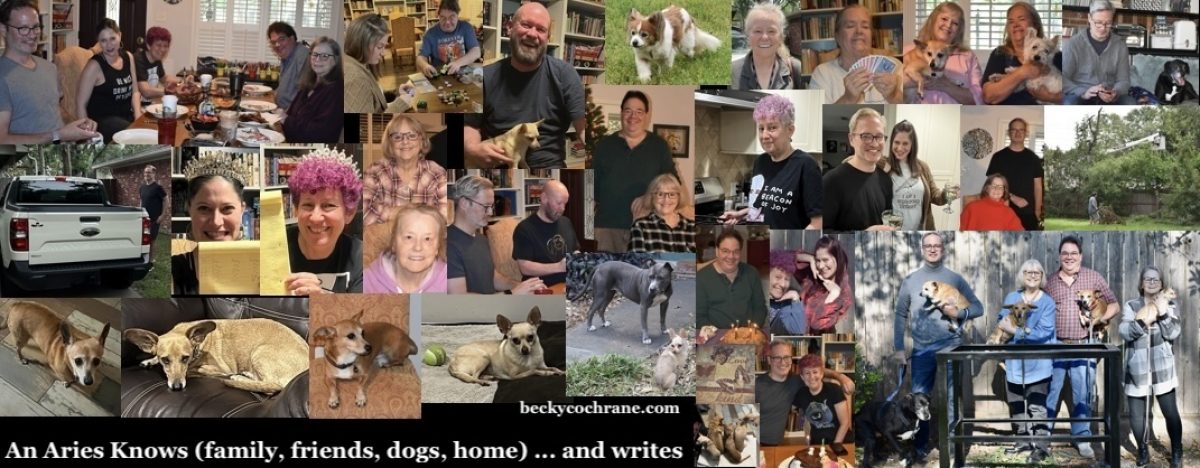

Thinking of Dr. Lineback and the things he taught us still manages to refocus my fear when we have tornado warnings in Houston. Last spring, when an EF-4 tornado destroyed a mile-wide, six-mile-long swath of Tuscaloosa, I wondered if current students had a Dr. Lineback of their own, or if some of his former students are still there and became part of the recovery efforts. I follow various social media sites to keep up with the city’s clean-up and rebuilding. I ordered these awareness bracelets for Tom and me–the houndstooth design used on them as well as on ribbons and other items is an homage to the houndstooth hat Coach Bryant always wore. But for me, the bracelets are also a reminder of Dr. Neal Lineback, who embodied the best that a university can offer its students and its city.

I do remember things from long ago. I couldn’t tell you Tom’s cell phone number now, but I can tell you my family’s phone numbers from my seventh through twelfth grades.

I do remember things from long ago. I couldn’t tell you Tom’s cell phone number now, but I can tell you my family’s phone numbers from my seventh through twelfth grades.