You may remember that last week was the tenth anniversary of my first meeting with Tim in our former favorite online chat room. My very first day online, my very first visit to that chat room, I met a woman named Tay from Southern California. It’s so great when two people meet and instantly connect–especially when time proves that the connection is real and enduring. Back then, Tay worked with an HIV/AIDS assistance organization. Our shared experiences taking care of and losing people we loved to AIDS was part of our immediate bond.

Later, Tay changed careers and began teaching middle school. I knew she’d be a dynamic teacher. If I had kids, she’s exactly the kind of teacher I’d want them to have. She’ll never feel like teaching is a matter of forcing knowledge into a kid’s head and then asking the kid to spit it back. A true teacher knows that for a few hours each day, you have the soul of a human being in your care–a human being who is much more than just a “learn this/behave this way” duty.

Effective teaching engages a child’s mind, heart, and body. Such is the goal of The Butterfly Project of the Houston Holocaust Museum. The project was inspired by a poem written by Pavel Friedman. Born in Prague, Friedman was deported to the Terezin Concentration Camp on April 26, 1942, and died in Aushchwitz on September 29, 1944.

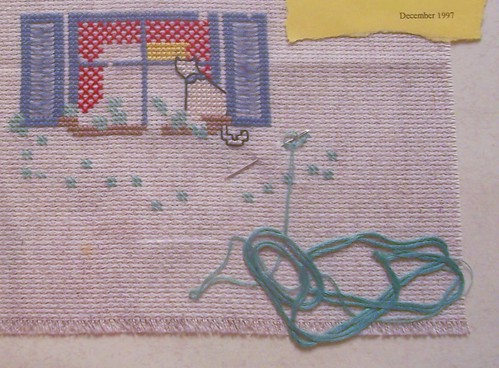

A total of 1.5 million children died in the Holocaust. The Houston Holocaust Museum hopes to collect 1.5 million butterflies to honor each of the victims. Tay’s students wanted to be part of this effort, so they learned about the children of Terezin. They made butterflies in their honor. They hung their butterflies in their classroom and shared stories with their fellow students about each child represented by an individual butterfly. Then they learned the fate of those children. If a child died, his or her butterfly was cut down.

I doubt there were many butterflies still floating over their classroom by the end of their project. In all, 15,000 children under the age of 15 passed through Terezin. Less than 100 survived.

By engaging their hands with glue and paper, feathers and sequins, colored markers and beads, ribbon and fabric, pipe cleaners and stickers, Tay took the hearts and minds of a group of Los Angeles children on a journey to the past to honor the lives and mourn the losses of children of the Holocaust. They remembered those who should never be forgotten.

I was honored that Tay sent the butterflies to me to watch over until she came to Houston. When Rhonda–who Tay and I initially also met in that same chat room all those years ago–found out that Tay would be going to the Houston Holocaust Museum, and that Tom and I would join her, to hand over the students’ butterflies, she found a particularly poignant way to say thank you to Tay and her students.

Rhonda’s parents are Holocaust survivors. They and other Houston area survivors included some of their memories and experiences in the book The Album: Shadows of Memory. Rhonda took a copy of the book to her parents and some of the other contributors and had them inscribe it to Tay’s students as a gift. Then she met us at the museum and accompanied us through a tour of the exhibits, sharing a part of herself and her family’s history with us.

It’s hard for me to admit that I have deliberately not gone to the Houston Holocaust Museum, just as I didn’t go to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. I know about the atrocities. Studying the history and literature of both World Wars was a huge part of my academic education, but also my education at home. My father was a WWII vet and a teacher of U.S. history and U.S. military history. I was an infant in my mother’s arms when she toured Dachau Concentration Camp, an experience that had a profound effect on her and which became part of my personal history as I was growing up.

When people say such horrors could never happen again, I usually shake my head and say, “We are always this close to it happening again,” and indicate a minute distance with my fingers. Every time we dehumanize a group of people, every time we close our eyes and ears to injustice and inhumanity, every time we refuse to do anything about genocide anywhere, we decrease that distance a little more.

I’ve always had to be cautious with how much information I take in about the Holocaust. Yesterday, Rhonda helped me understand that if a gift can be taken from this part of our past, it’s knowledge of the amazing will of people to survive, of our resilience, our determination to endure and to emerge from such an experience still able to live with joy, to love, to give life to new generations.

And Tay and her students helped me remember that our greatest hope lies with the willingness of children to be much fairer, much wiser, much kinder than some of the adults who’ve come before them.

Whatever our anguish, however deep, hope is its butterfly.

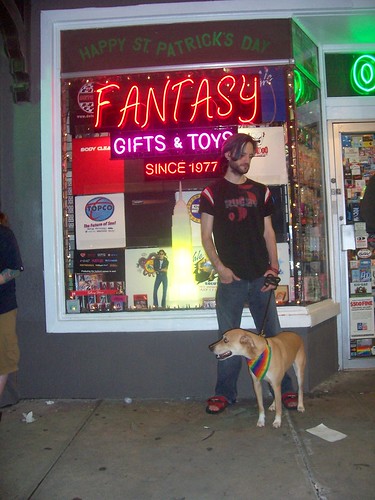

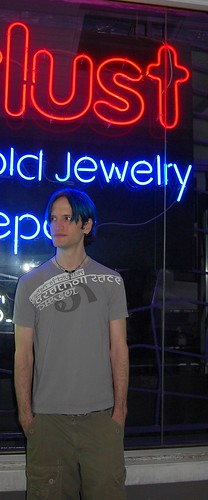

For more photos, click on the picture, then go up to the gallery.

(Some of the photos have notes. A photo can also be clicked on to enlarge if you need to see it in more detail.)