I’m a good cook. That isn’t bragging, because what I mean by it is that I have a few dishes I’ve learned to do well over the years. I can follow the directions of a recipe. I rarely attempt anything that’s too complicated, because it doesn’t usually end well. I’m a good cook of simple Southern fare, and fortunately that’s okay, because most of the people who come to The Compound table want simple Southern fare.

I found myself thinking this morning that today, I cooked much like the generations of Southern women who taught me. I slow-cooked a roast overnight and put it in the refrigerator when I woke up, then added potatoes and carrots to its juices also to cook slowly. My sides of black-eyed peas and salad were done before the worst heat of the day set in and made the kitchen intolerable.

I’d planned to bake brownies anyway, so since I had an overripe banana, I also put a loaf of banana bread in the oven to bake.

Now it’s all done and I just need to do a bit of light housekeeping before I can shower and read or write or pester the dogs in some way (brushing–only Rex truly loves the Furminator–or singing to them, or withholding treats because they think they’re entitled to those 24/7).

While I was cooking, I thought of my first husband’s grandmother, Granny. I’ve said before that I was lucky both times I married to acquire grandmothers, since my own died either before I was born or when I was very young. Though I remember sitting outside my grandmother Miss Mary Jane’s kitchen door while she cooked, I wasn’t old enough to be of any help. But as an adult, I visited Granny at her house in the country and learned all kinds of helpful kitchen tips. Every single Sunday she laid out a feast for her children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren, including at least a couple of meats (roast, ham, chicken, game), endless bowls of vegetables, biscuits, cornbread, rolls, and an entire table just for cakes, cobblers, and pies. Granny did it all by hand and from scratch–yes, including her cakes. I would watch and marvel and assure her there was no way I’d attempt a cake without a mixer, and she’d hold up her wooden spoon with her strong right arm and say, “I’m stout.” What she taught me has become so ingrained that I’d have a hard time differentiating between what I learned from her, my mother, my sister and sister-in-law, my friend Debbie, and Lynne and her mother, aunts, and sisters. A couple of things I do remember about Granny: She would make a yellow cake layer in a skillet just like cornbread and leave it unfrosted. Her grandson called it “corn cake” and would eat the entire thing if she’d let him. I also remember that the secret to her mashed potatoes was replacing milk with mayonnaise.

My father could not cook–he burned everything–but I think there was a method to his madness, because he’d much rather have eaten his wife’s or daughters’ meals. In his defense, he was a masterful maker of sandwiches, and no cole slaw I’ve ever had has been as good as his. Tom can cook but would rather not, so he mostly just gets stuck with steaks, checking fish for doneness, and cooking stroganoff. I dated one guy who had what I think are true culinary skills–he was inventive and intuitive. I still have one of his recipes for crab au gratin, but mine never turns out like his and has at times even been a spectacular failure, so I don’t cook it anymore.

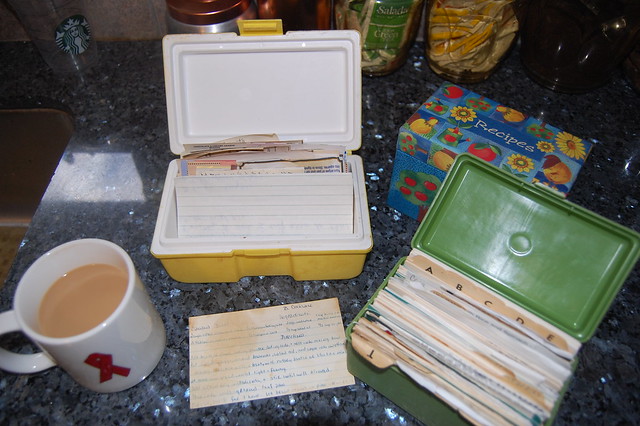

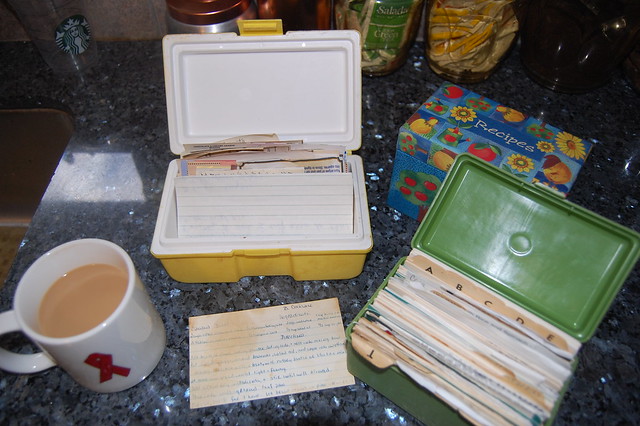

I would not trade all those times in kitchens with the women in my life for anything. I often wonder if young people now are so into cooking classes because they were raised in families where both parents worked, grandparents lived far away, and dinner was likely to be something that was picked up or taken from the grocer’s frozen prepared foods section to the oven. I think reality shows have helped encourage people to see cooking as something more than drudgery. I see lots of magazine kitchens with a computer handy for looking up and saving recipes online. Smart and efficient, but the other thing I wouldn’t trade are my recipe boxes. Whenever I open them, it’s like opening a door to wonderful memories. There is Mrs. Lang’s delicious sour cream chocolate cake recipe, way too ambitious for me to bake, but written in her beautiful cursive writing over several index cards that she ingeniously taped together to unfold like a little book. Cards for Toota’s cheese straws, Uncle Austin’s brownies, Aunt Audrey’s hushpuppies, Katie’s chocolate chip oatmeal cookies, Lynne’s rum balls, Vicki’s fruit pizza, Mary’s pumpkin pie, Mother’s pecan pie, summon up endless scenes of baking and laughing and arguing about ingredients and taste testing.

The yellow box is my mother’s and contains a completely unorganized batch of her recipes. I leave them the way she had them because then they’re like clues to a life–what she cooked most, which ones got shuffled to the back in cooking exile. The green box is the one she bought me when I took Home Ec in ninth grade, and it got so full over the years that I had to separate some categories into that bright cardboard box. I could easily thin them out, because they include all the recipe cards I had to fill out by hand in all the categories assigned to us by Mrs. Woods, but that would feel like saying goodbye to a young girl who still lives inside my skin. I remember my mother rolling her eyes at some of the recipes I copied from her cookbooks–who, after all, is going to make chocolate pudding from scratch when there’s Jell-O?–but I was just doing my homework, not planning future menus (the point of the assignment, I’m sure). When I look at my recipe for chocolate pound cake, I remember that’s what I was making for a class assignment at home on the night I got my first migraine ever–the whole event including aura, numbness over half my body, unbearable headache, trembling hands, disorientation, and nausea. I don’t think the two events were connected, it was just chance. I was certain I was having a stroke or brain aneurysm or something soap-opera fatal, and my mother ordered me out of the kitchen to bed and finished the cake for me. It wasn’t deliberate on my part, but it was a move I’m sure my father would have applauded.