One of the panels I attended at Saints and Sinners was titled “The Devil You Don’t Know: Otherworldly Forces in Fiction.” The description from the program: The force of evil in a work of fiction often appears in an otherworldly guise to distill the author’s intent with his or her terrifying character or object. However, evil obviously exists in more realistic forms in the world around us every day. This panel will focus on how different writers represent ideas of evil or horror and how the supernatural may be used and blended with realistic events in order to create a force which speaks to the power of evil in the world.

Though I’ve considered writing romantic suspense and perhaps something paranormal, I don’t read horror and genuinely don’t plan to write horror. It would be easy to say I attended this panel to support ‘Nathan, who’s not only a friend but a contributor to both Fool For Love and Foolish Hearts. But I’ve found that no matter what genre authors write in, they all have insights and guidance that can benefit any writer. And this was a panel that would reintroduce me to writers whose work I already know, ‘Nathan Burgoine and Christopher Rice, as well as new-to-me authors Christian Baines and Marie Castle. Plus it was moderated by Jean Redmann, who always has interesting observations.

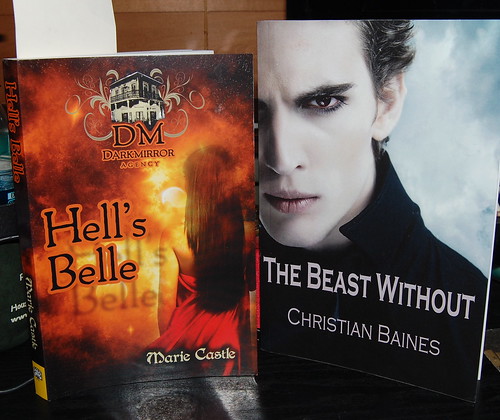

For people who write about evil, these were some relaxed and humorous panelists with lots of wisdom to offer, including how perhaps growing up feeling like “the other” because of their sexual orientation led them to explore the otherness of monsters or those with magical powers in their writing. ‘Nathan’s current novel Light, a Lambda Literary Award finalist, has as a protagonist a gay superhero with psychokinetic and telepathic powers. Chris Rice’s current title, The Heavens Rise, is a supernatural thriller about the return of an ancient parasite that threatens the future of humankind. Christian Baines’s The Beast Without is the story of a Sydney vampire who has to form an uneasy alliance with other supernatural beings to deal with a rogue werewolf. Marie Castle’s Hell’s Belle, the first in her Darkmirror series and also a Lambda Literary Award finalist, is the story of a witch whose family guards the gates that keep demons and their ilk from leaving the Otherworld and coming into our world.

In the South, a story never starts where it should. Ask a man why he killed his neighbor, and he might start by saying, “Well, I had Cream of Wheat for breakfast then put on my favorite flannel shirt…” An hour later, he’ll get to the point. This is why you never ask a Southern man why he doesn’t love you. The answer usually starts when he was five and continues on through every previous love.

Christian, who has a delicious accent–if his vampire Reylan sounds like that, it’s easy to hear how he charms his prey–read these first lines from his novel:

On any given night, in any city in the world, somebody will die before sunrise and most of them will die alone.

I found the opening intriguing, and I’ve since read the entire book, and oh, how I loved the below passage from a scene when Reylan–who, by the way, prefers to be called a Blood Shade and abhors the word “vampire”–must go to a club that he can’t stand, full of emo and goth kids costuming themselves like those monsters they think are only fantasy. Because I know how so many of you mock my enjoyment of a certain shiny vampire, this is for you:

A menagerie of every horror cliche you could imagine met my eyes as I scanned the room. Though in fairness, what the costumes lacked in originality, they typically made up for in craftsmanship. No common Halloween trash. These people knew their genre and lavished it with sincere affection… There were a number of imitation Blood Shades, some of whom had even done well enough to leave the Stoker and Rice imagery behind. I allowed myself a satisfied smirk until I saw…Ugh. There had to be one. No more than a teenager. His skin, sparkling as it caught the club’s pulsing lights.

Don’t.Start.Me.

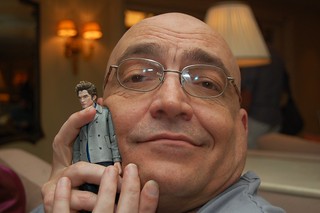

(A comment Greg Herren made on a different panel made me caution him that I had a little vampire traveling with me all the time who hears all. Greg reminded me that he hadn’t said anything negative about my vampire, and then posed with Little Edward to show there were no hard feelings.)

(A comment Greg Herren made on a different panel made me caution him that I had a little vampire traveling with me all the time who hears all. Greg reminded me that he hadn’t said anything negative about my vampire, and then posed with Little Edward to show there were no hard feelings.)

One of the things Christopher Rice mentioned is how these stories, much like the fairy tales of old, are cautionary tales we create to give us an illusion of staying safe and being in control of our lives. ‘Nathan touched on that, too, in that his characters can fight back and use their voices in defiance of the silence and oppression people may experience in real life. There are many reasons why we turn to fantasy, science fiction, horror, and paranormal books–and sometimes the romances contained therein.

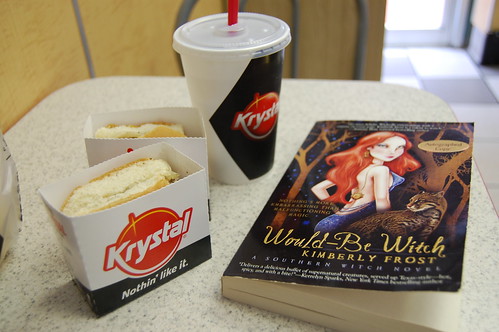

Lots to think about…just as I’d expected, and I don’t need to write horror to apply some of their wisdom to the things I do write. I had taken the first of Kimberly Frost’s Southern Witch series with me to New Orleans to reread. I finished it there and began the second one. After I’d finished rereading the first three, I downloaded the novella that comes between Books 3 and 4, “Magical Misfire,” then I was finally ready to read Slightly Spellbound. Now I have to wait a year for the next one! If you click on the link to Kimberly’s blog, she’s got a giveaway going right now, and you can read the details there.

Happy reading! Or–chills and thrills, if you prefer those.

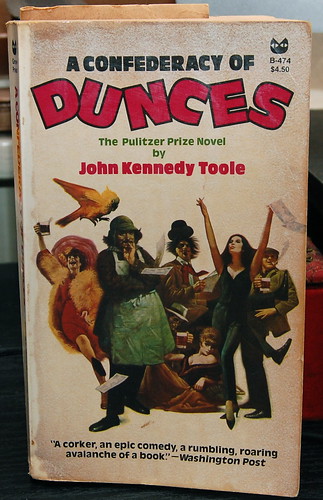

Through the years, my brother has recommended many good books to me. Some of them were tough reads, and what I’ve learned about highly recommended tough reads if I give up on them is that I should revisit them sometime later. A lot of books that I adored as a young adult didn’t have the same luster when I reread them after getting older, so I assumed, correctly, that the opposite could be true. Some books just have to come along at the right time in your life, which is why I continue to reread a lot of the classics that bored me (especially as a teenager). As an adult, I’ve understood how brilliantly they were written and could appreciate them on a level that was beyond me as a youngster.

Through the years, my brother has recommended many good books to me. Some of them were tough reads, and what I’ve learned about highly recommended tough reads if I give up on them is that I should revisit them sometime later. A lot of books that I adored as a young adult didn’t have the same luster when I reread them after getting older, so I assumed, correctly, that the opposite could be true. Some books just have to come along at the right time in your life, which is why I continue to reread a lot of the classics that bored me (especially as a teenager). As an adult, I’ve understood how brilliantly they were written and could appreciate them on a level that was beyond me as a youngster.

Sometimes Sonny felt like he was the only human creature in the town. It was a bad feeling, and it usually came on him in the mornings early, when the streets were completely empty, the way they were one Saturday morning in late November. The night before Sonny had played his last game of football for Thalia High School, but it wasn’t that that made him feel so strange and alone. It was just the look of the town.

Sometimes Sonny felt like he was the only human creature in the town. It was a bad feeling, and it usually came on him in the mornings early, when the streets were completely empty, the way they were one Saturday morning in late November. The night before Sonny had played his last game of football for Thalia High School, but it wasn’t that that made him feel so strange and alone. It was just the look of the town.